Notes on a Unified Culture

My trip to the Capital

I reserve my judgment for when I travel, perhaps subconsciously, with the understanding that my momentary vitriol translates to a sweeter return home. I am a purist, I suppose, for the place in which I reside: a misanthropic plateau, such that wherever I go I will have something about which to complain. I am always home if I hate where I am. I have spent the last four days in a suburban area of Arlington, Virginia, just outside of Washington D.C. I went into Washington D.C. for a few of these preceding days because there is very little to do in Arlington, Virginia without federal intelligence clearance. My digital footprint guarantees that I would never pass the famously thorough background check.

The Metro train line connects Arlington to D.C. to some of greater Maryland across the Potomac River. Despite only connecting a small region of land, the area surrounding each stop has a fragmentary feeling; it’s a strange revelation considering the monolithic projection that the nation’s capital seeks to project. On the Metro, one hears “Next stop, Pentagon…” spoken with robotic mundanity as a reminder (mostly for tourists) that our government is not a removed entity, but instead a figure within reach of its populace (or perhaps its populace within reach of it. I am old enough to remember the panic surrounding the consolidation of the NSA’s power to monitor American citizens, though I was only old enough to get most of my information about it through MAD Magazine). The capital did not have the look of the high-security-shadow state that I knew it to be. People mingled freely and easily with national monuments. If the Guard was present, their presence was not known. Far from the polished neoclassical architecture I was used to seeing, the whole place was closer to urbanized corporatism.

“Next stop, Pentagon City…” one hears on the Metro. Pentagon City is a large mall across the highway from the Department of Defense. “Transfer here for Macy’s, Nordstrom, and California Pizza Kitchen.”

I spent a significant amount of time in Crystal City, the neighborhood that housed a location of the climbing gym franchise I attend. Billed on Google as a trendy, up-and-coming neighborhood, Crystal City was completely empty. There were high rises, many high rises, though the status of their occupancy was questionable. Some may have been apartments with permanent residents, but it seemed to mostly be hotels for temporary stay near D.C. The scene was reminiscent of the sweeping scenes of brutalist industrialism in Jacques Tati’s Playtime: concrete impositions of hotels and office buildings against the Parisian skyline. Similarly, one sees the sign for Crystal City’s Crowne Plaza, and in the distance the tip of the Washington monument just over the Potomac.

Upon trying to describe Crystal City to people unfamiliar with it—because anyone that was already familiar had their own, similarly distasteful opinion of it—I would settle on the word “apocalyptic” to describe it. Not apocalyptic in the sense of destruction, but the quietly apocalyptic phenomenon of suddenly realized singularity. To walk the streets of Crystal City was to make sudden, unwitting acquaintance of one’s own companionship. Even a short stretch of sidewalk could feel endless with the rolling array of vertical windows; “nothing ahead, nothing behind” beats like a metronomic mantra for the pedestrian, only remaining unassailed by the hope that the arrival at their destination means people will be present.

When I spoke to my uncle about Crystal City’s emptiness, he said that it had been like that for decades. “Some revitalization projects are being done to get people to come to that area,” he said, “But it never really had vitality in the first place.” Their strategy befit the culture of today’s urban development: give a neighborhood a climbing gym and the rest will fall into place.

The gym was located beneath a mall connected to another hotel. It was the most populated place in the entire neighborhood, like a society of people that had been driven underground. Next to the door in and out of the complex was a fountain outfitted with beer taps and a sign that said “Fill your bottle, pay per ounce!” If I found myself filling a reusable bottle at one of these pay-per-ounce stations, I would think my substance use had crossed a line and I would want to seek counseling. Crystal City, built around an uncanny assumption of an archetypal “hip, young person” stands as an indictment to the balmy ethos of the planned adult playground. In a moment one could be alone in the world, surrounded by delights and nobody to enjoy them with. How American.

I realized then that I understood very little about D.C. In avoiding the typical spots for tourism (I had already seen the heritage sites on a middle school field trip to the East Coast. I would spend a year in Crystal City over an hour-long guided tour of Gettysburg), I found myself in the remnants of a corporate Bacchanalia, perhaps to remain empty, perhaps to find longevity with a corporate takeover. But I found no people, and I felt nothing.

The security line at the airport for my trip home moved slowly, much slower than I expected for a Monday flight. The man behind me in line had a U.S. House of Representatives tag on his luggage and the look of a Congressman: permanently flushed skin, formal dress for a domestic flight, and his white hair slicked directly upward, as if with his own spittle. I had to speak with him.

“I didn’t expect it to be this crowded for a Monday,” I said. He breathed in deeply.

“They have a guy just sitting there,” he began, motioning to a TSA agent sitting at the entry point of a closed security lane. Much of the reason that we had been stuck standing in one place was the fact that only one lane was open and that travelers that paid for CLEAR were being shepherded through before us. He continued to speak in the slow, practiced cadence of someone who has orated on the topic many times.

“The reason socialism does not work is that people are not rewarded for doing good or punished for doing poorly. This is the reason free market capitalism works: people are rewarded for treating others well and punished for treating others poorly, and it has only been that way since forever.”

Perhaps he felt the need to say this to me because he saw that I have a nose ring. Perhaps this was an outpouring of the burbling McCarthyist rhetoric he one day staked his political career on and never had to shift. I knew one thing to be true: the security line was the most reductive model of free market capitalism that could be crafted; CLEAR isn’t on a random voucher basis.

So I said “Oh okay.”

The security lane opened up, and we lost sight of one another.

Being in D.C. so close to the election, it has been difficult to avoid the question of unity, of whether it is possible, of whether it has ever been a value that the nation aspires to. Take, for example, the man behind me in the security line. I can say confidently that I would never seek out his company, and likely never want him to represent me (I prefer my elected officials to have a functional knowledge of economics and history). Yet there we were: carriers of the same passport, possessors of the same nationhood, polarized citizens meant to determine a semblance of government.

In the introduction to his book American Nations, Colin Woodard writes:

“Our divisions stem from this fact: the United States is a federation comprised of the whole or part of eleven regional nations, which truly do not see eye to eye with one another [...] Few have shown any indication that they are melting into some sort of unified American culture.”

“Unity” is pervasive as a platitude, but feels totally unachievable as material reality. It works better as balmy marketing copy, a word to be trotted out every four years by corporate America and retired promptly by December for Christmas, then whatever popular sentiment follows it. I will end on some thoughts regarding the very example of what I’m referring to:

I first came across the “Unity Kombucha” while scrolling through my feed on the social network “X.” Somewhat ironically, this website is infamous for everything from attempting to destabilize Latin American elections through the spread of misinformation, to the resurgence of skull phrenology. Yet there was a promising picture: a bottle with a blinding white label and a central graphic of a blue hand and a red hand clasped together. Tattooed along their arms are a pattern of tiny dancers, like bootlegged Keith Haring figurines (Is this a promising sign? The Keith Haring Estate’s collaboration with UNIQLO was the closest our culture came to unequivocal queer acceptance). One need not possess a degree in the higher studies of semiotics to understand it.

A drink boasting “unity;” it was certainly the right moment for it to hit the market in our culture, though not necessarily a novel idea. Find a recent example in Kendall Jenner’s infamous 2017 Pepsi commercial, in which police and a group of Black Lives Matter demonstrators are deterred from clashing violently over the sharing of an ice-cold Pepsi presented by Jenner. The advertisement was universally panned for being tone-deaf and reductive.

Kombucha is an odd choice for a drink to foster connection across a divided culture; it possesses an inherent classism (I did buy it at Whole Foods, after all). Kombucha means different things to different people in America. When brewed in San Francisco, it can be spun from a cottage industry into a national empire, like the story of GT’s Living Foods, the very company that made this one. When brewed in Appalachia, it’s called moonshine and it carries a fine of up to $1,000 for the first offense. Why over-complicate the mission? The same effect of unity could be achieved by two voters on the opposite side, sharing an emulsification of 7-Up and Klonopin.

But the culture today is meaner, more divided than ever, and more desperate to be reunified. Was Kendall Jenner simply ahead of her time?

The flavor profile is distilled down to three ingredients listed on the front of the bottle: Cherry, Lemongrass, and Coconut. Upon first sip, I can immediately taste all of the flavors because it’s an inoffensive combination. Obviously it has a pleasant taste; it’s basically a Shirley Temple. Had they really wanted to make a statement, they should’ve found serendipity in truly unexpected combinations of flavor. Give me California fennel and a Georgia peach. Give me organic tomato juice and DDT. Give me liquified stem cells and gun oil!

No, instead Unity kombucha offers a beverage experience comparable to the poolside bar on a Carnival Cruise ship, at only a marginally lower price (Quite frankly, the Carnival Cruise may be the last great melting pot of all American peoples. Perhaps this was intentional). It’s weak-bodied, even for a mass-produced kombucha. After the initial punch of sweetness, there’s little that lingers in the mouth; no sourness, no bitterness, no indication that the coveted probiotics I’d paid for are about to enter my body. The terroir is that of an intensively sterilized environment. Obviously kombucha must be brewed in a sterilized environment, but this is a different sterility, that of a fluorescently lit focus testing room. This tastes like the result of an intensively guarded laboratory process for a product that could have mass appeal across a divided culture. “Towards a Radical Middle” declared Renata Adler in her essay titled with the same phrase. “Towards even less!” replies GT Foods.

Given its simple flavor profile, the drink is finished in a matter of minutes. It’s like soda: unbearably saccharine, just like the message adorning the bottle. Next to the nutrition facts is a message from the company’s founder:

“Inside this bottle is a synergistic symphony of beneficial microorganisms working in concert to create the perfect kombucha. As I hold hands with my brothers and sisters, we are connected through love, compassion, and kindness. Our bond is built with respect and equality, for we are stronger together than apart. The power of our unity allows us to overcome adversity, negativity, and division.”

The passage is crammed full of buzzwords that amount to much less than the content itself. But it reminds us that despite our differences, we are all the same deep down in the pits of our stomachs.

Would the man with the House of Representatives bag tag enjoy Unity Kombucha? It was a product of the free market. Crystal City was as well. I left without much new to say about unity, but I know that I have not yet been too melancholic to take the piss. With the impending election, I will leave on this note: let us not be judged for our outer qualities, but for the contents of our microbiome.

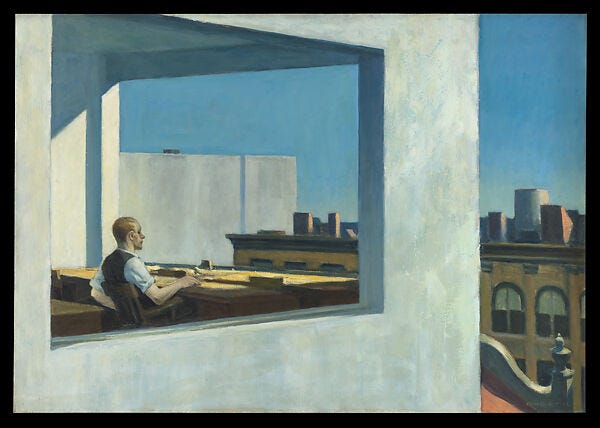

Image credit: Office in a Small City by Edward Hopper, sourced here.